By Mookie Harris, Lead Interpreter in Dinosphere® and National Geographic Treasures of the Earth

Juneteenth celebrates the end of slavery in the United States in 1865 and is considered the longest-running African American holiday. It’s a great day to celebrate Black culture and history, especially the mostly overlooked contributions of enslaved African people.

The majority of these people were brought into the port of Charles Town, Carolina, which is now known as Charleston, South Carolina. About 17 miles outside the city, there was a large plantation called Stono. Around 1725, an English naturalist named Mark Catesby was visiting Charles Town and heard about an amazing discovery at the Stono Plantation.

The discovery

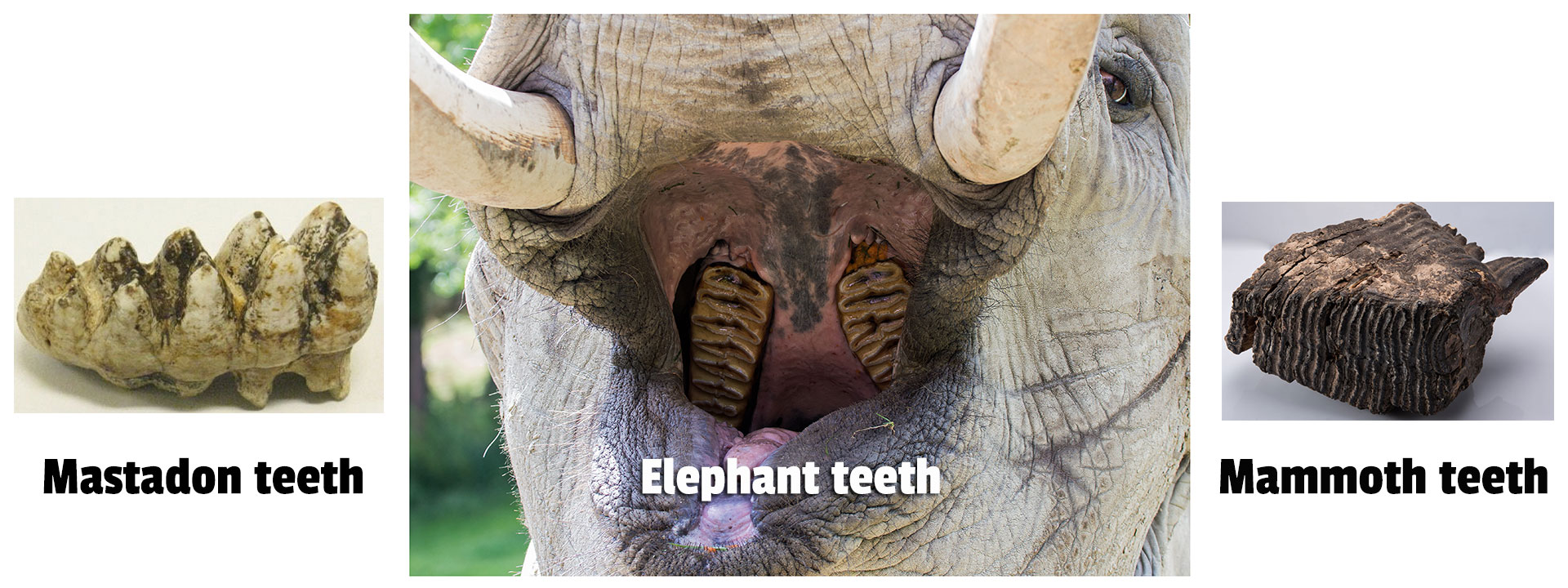

Enslaved people working in the swampy fields of Stono had found some huge mysterious teeth. Catesby paid a visit to Stono and spoke to the owners who showed him the gigantic molars. They weren’t sure what kind of creature the teeth came from.

But Catesby also spoke to the enslaved Africans. Most of them had lived in Congo and Angola prior to being taken to the New World. They were all in agreement that these were elephant teeth, just like the ones they were used to seeing in their homelands. Catesby agreed with them because he had studied the molars of an African elephant in London.

TradingCardsNPS, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

TradingCardsNPS, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Catesby sent word of the discovery to French naturalist Georges Cuvier in Paris, who had been studying the fossils of mammoths and mastodons. Many people at that time thought that fossils were from species that were still alive in some remote, undiscovered place on the planet, but Cuvier had been theorizing that fossils from mammoths and mastodons were from extinct animals similar to modern elephants. Cuvier was very impressed that the Africans at Stono had recognized these teeth as being similar to elephant teeth before any European naturalist had made that connection.

Paving the way

These Africans had not only made the first recorded vertebrate fossil discovery in America, but they had correctly identified it as being from an elephant relative. This discovery led to Cuvier’s concept of comparative anatomy and his 1796 hypothesis that the Earth periodically went through sudden changes, each of which could wipe out a number of species and that the fossils he and several others were just beginning to study were the remains of “a world previous to ours.” In turn, that led to Cuvier establishing the field of paleontology, the study of prehistoric life based on fossil clues.

As we celebrate this historic day when slavery ended in the United States, let’s also celebrate the fact that many of the people who were enslaved made large contributions to history. It’s up to us to make sure that their stories don’t get erased.

Mastadons, mammoths, and elephants

By the way, mastadons and mammoths are both related to elephants, but there are some big differences between them. One of those differences is in the way their teeth are shaped. Mammoths had teeth with ridged grinding surfaces for eating grassy vegetation the same way that elephants do today. Mastodons are not as closely related to elephants as mammoths. They had cone-shaped bumps on their teeth that allowed them to eat branches, twigs, and leaves.

Both of these Ice Age animals lived all over what is now the United States, including right here in Indiana. They went extinct around 10,000 years ago. The next time you visit The Children’s Museum, head up to Level 4 and check out the teeth on our mastodon and see what you can learn from studying its fossils.

SOURCE: Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Finds of the First Americans. Princeton University Press, 2007

(

(